This topic takes on average 55 minutes to read.

There are a number of interactive features in this resource:

Biology

Biology

Science (applied)

Science (applied)

Enzymes catalyse reactions by lowering the activation energy needed for the reaction to take place. How do they do this?

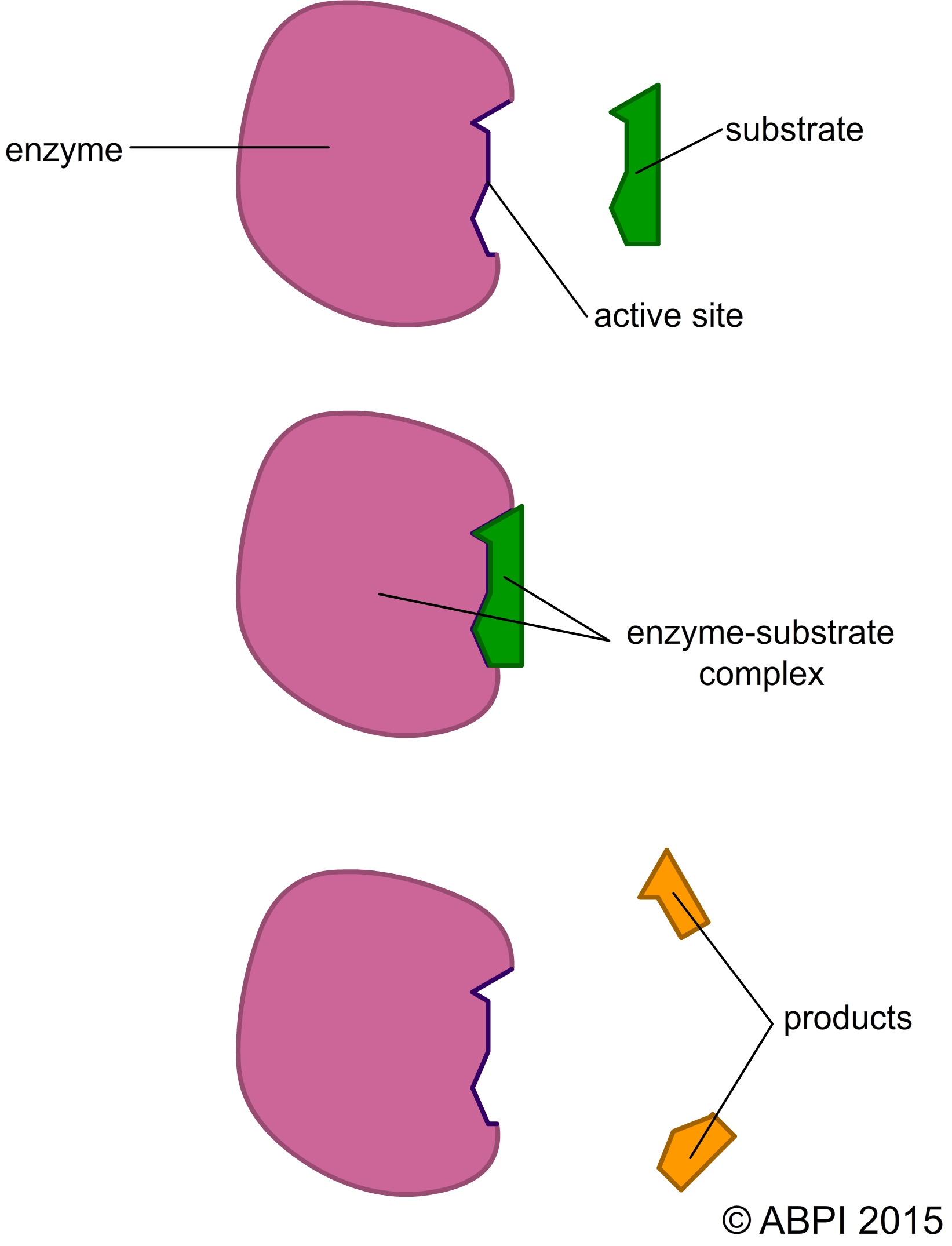

The substrate of the reaction binds to the active site of the enzyme to form an enzyme-substrate complex. Intermolecular bonds such as hydrogen bonds form between the active site and the substrate, holding it in place.

enzyme + substrate(s) → enzyme-substrate complex → enzyme + product(s)

When the products have been formed they have a different chemical makeup and 3D shape so they do not form the same hydrogen bonds with the active site. They are released from the active site and the enzyme is free to bind to more substrate molecules (see Chemistry of Life).

We have two different models to explain how the structure of an enzyme is related to its function in catalysing specific reactions:

The lock-and-key hypothesis assumes that the active site of the enzyme has a specific 3D shape that fits the shape of the substrate exactly. As you have seen, only one substrate or type of substrate will fit the shape of the active site, and this gives the enzyme its specificity. There are a number of hypotheses about how this binding to the active site can lower the activation energy and bring about catalysis.

Once the reaction has been catalysed, the products are no longer the right shape to fit in the active site and the complex breaks up. The products are released and the enzyme is free to catalyse another reaction.

The lock-and-key hypothesis fits many of the observations made on enzyme activity see (see next page) but recent evidence from X-ray crystallography and chemical analysis of active sites suggests the situation might be rather more complex.

The lock-and-key hypothesis of enzyme action.

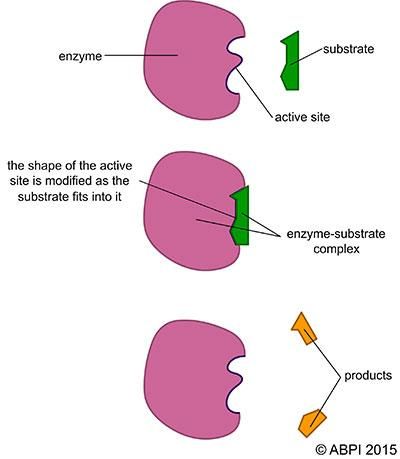

The lock-and-key hypothesis assumes the active site is rigid and set. In the induced-fit model, the active site is visualised as having a defined but flexible shape and arrangement. This suggests that as the substrate enters the active site, the shape of the active site changes to fit tightly around and bind to the substrate. When the products leave the complex, the enzyme returns to a relaxed, inactive state until another substrate molecule binds to it.

The induced-fit hypothesis of enzyme action.