This topic takes on average 55 minutes to read.

There are a number of interactive features in this resource:

Biology

Biology

Developed by Edward Jenner in 1796, vaccination has made a major contribution to the fight against infectious diseases. It prepares your body's immune system to prevent infections from diseases such as measles, mumps, rubella, polio and tetanus.

When you are vaccinated, you are given the pathogen that causes the disease, or even just some harmless fragments of it. It is safe because it contains pathogens that have been killed or weakened so that they do not cause an infection. Vaccines can sometimes be given by mouth or an injection. Sometimes more than one vaccine is given at the same time. This is the case in the MMR triple vaccine (measles, mumps and rubella) which are contained in a single injection.

How vaccination works.

Your immune system detects the foreign pathogens and mounts a primary immune response against them even though they will not cause an infection. It takes a little time for your lymphocytes to make antibodies against the pathogen and during this time, they also build up a large number of memory lymphocytes. These remain in your body for many years and are constantly ready in case of re-infection with the living pathogen. When this happens, they can quickly produce a large amount of antibodies and kill off the infection before any symptoms are seen. You have an immunity against the disease.

With some vaccinations, the immune memory can reduce over several years. Infections like tetanus may need booster vaccinations over a period of time to refresh the memory lymphocytes.

Each vaccination provides immunity against that particular disease and so a programme of vaccinations is given to provide immunity against a range of common infections. The introduction of vaccines has changed the occurrence of disease around the world. Smallpox has gone completely, and polio only remains in a tiny handful of countries. Diseases like diphtheria which used to kill thousands each year in the UK are now almost unheard of. Diseases such as whooping cough are rare. Once a successful vaccine for a disease becomes available, that disease will no longer occur, or become very rare, wherever the vaccine is used in enough of the population to give herd immunity.

A small child receiving an oral polio vaccine in Ethiopia.

Courtesy: World Health Organisation (WHO) / P. Virot

It would be ideal if there was a vaccine for all infectious diseases. Sadly it is not possible in reality, at least with the science we have at the moment.

Some diseases, like influenza and the common cold, are caused by viruses that mutate and change year-by-year. They show different antigens on their surface. A new influenza vaccination needs to be given each year when the new strain of the virus have been identified. The cold virus mutates too quickly for a vaccine to be produced and used.

It is also more difficult to make successful vaccines against some diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, and so research continues into the production and testing of new vaccines.

The benefits of vaccinations are enormous. In the UK alone millions of people are alive and well because they no longer suffer from smallpox, polio, diphtheria, tetanus or any of the serious and often fatal illnesses which used to kill hundreds of thousands of adults and children every year. In fact, vaccines have been so successful that people often forget just how dreadful all these diseases really were.

Vaccines, like every medical treatment, have a slight risk linked to them. Like all medicines they are tested at length before they can be used, and they are checked constantly once they are being used.

In spite of all this care, sometimes people suffer from bad reactions. These range from simple things like a sore arm after the injection, a mild fever or a rash to more serious symptoms.

It is very difficult to link an event with a vaccine. For example babies have vaccinations several times during their first year of life - and so by simple coincidence they may well suffer from some symptoms of illness in the few weeks after they have been vaccinated. Naturally parents worry that the vaccination has caused the symptoms - but a real link is only shown very rarely indeed.

Between 1990 and 1995 in the UK, there were 5433 suspected adverse reactions to all the vaccines given to children under 15 years of age - out of around 80 million doses of vaccine - that's 0.00008% of cases. Only a tiny number of those were serious.

In the late 1990s a UK doctor caused a scare about the safety of the MMR vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella. He has since been completely discredited and struck off the medical register - but as a result of his bad science, worried parents stopped taking their children for the MMR vaccine, many children became seriously ill and a small number died as a result of measles and mumps. People should perhaps have known better - there was a similar scare story about 20 years earlier.

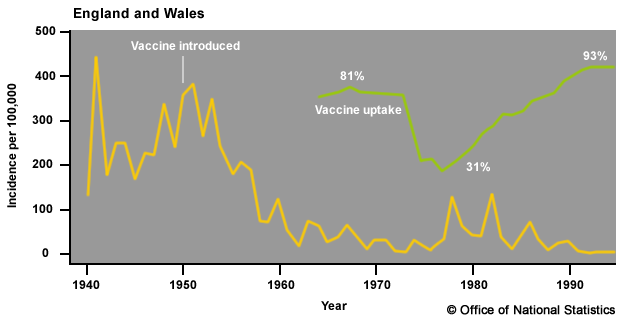

In the mid-70s Dr John Wilson published a report based on 36 patients suggesting that the pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine might cause brain damage in some children. The media publicised the story and parents began to panic. The number of children being vaccinated against whooping cough fell from over 80% to below 50%.

Unfortunately, in their fear of the vaccine people forgot that whooping cough itself causes both brain damage and death. In Scotland alone about 100 000 children suffered from whooping cough between 1977 and 1991 - and about 75 of them died. The same thing was seen across the UK.

Whooping cough can cause brain damage and even kill.

Courtesy of CDC

Whooping cough figures and vaccination levels following the scare

When the original research was investigated, it was found to have serious flaws. Identical twin girls who were included in the study, and who later died of a rare genetic disorder, had never actually had the whooping cough vaccine. Only 12 of the children investigated had shown any symptoms close to the time of their pertussis vaccine, and the parents were involved in claims for financial compensation from the vaccine manufacturers.

The judge who heard all the evidence in the compensation claims was convinced that the risks of whooping cough far outweighed any possible damage caused by the vaccine, and he severely criticised both the scientist and the study. However the media were not very interested in this part of the story. It was 20 years before vaccination levels, and therefore levels of whooping cough, returned to the levels before the scare. Vaccination uptake is now well over 90%, and deaths from whooping cough are almost unknown in the UK.