This topic takes on average 55 minutes to read.

There are a number of interactive features in this resource:

History

History

Biology

Biology

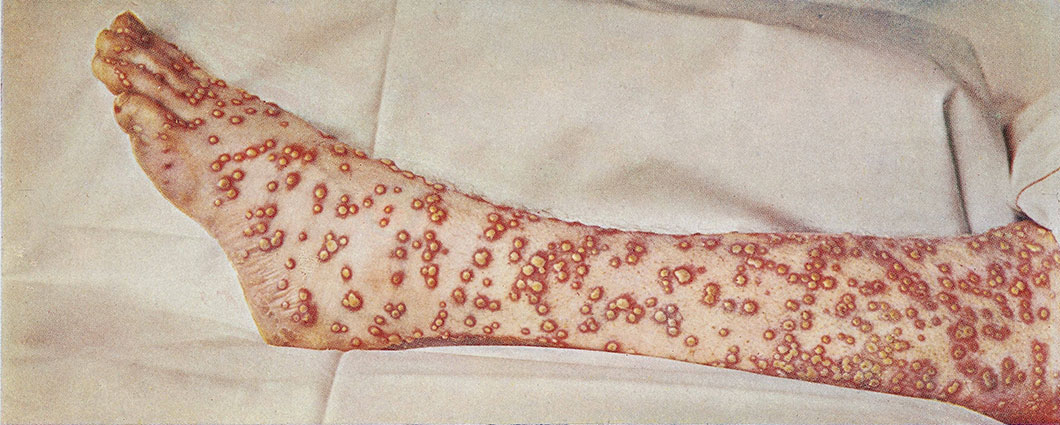

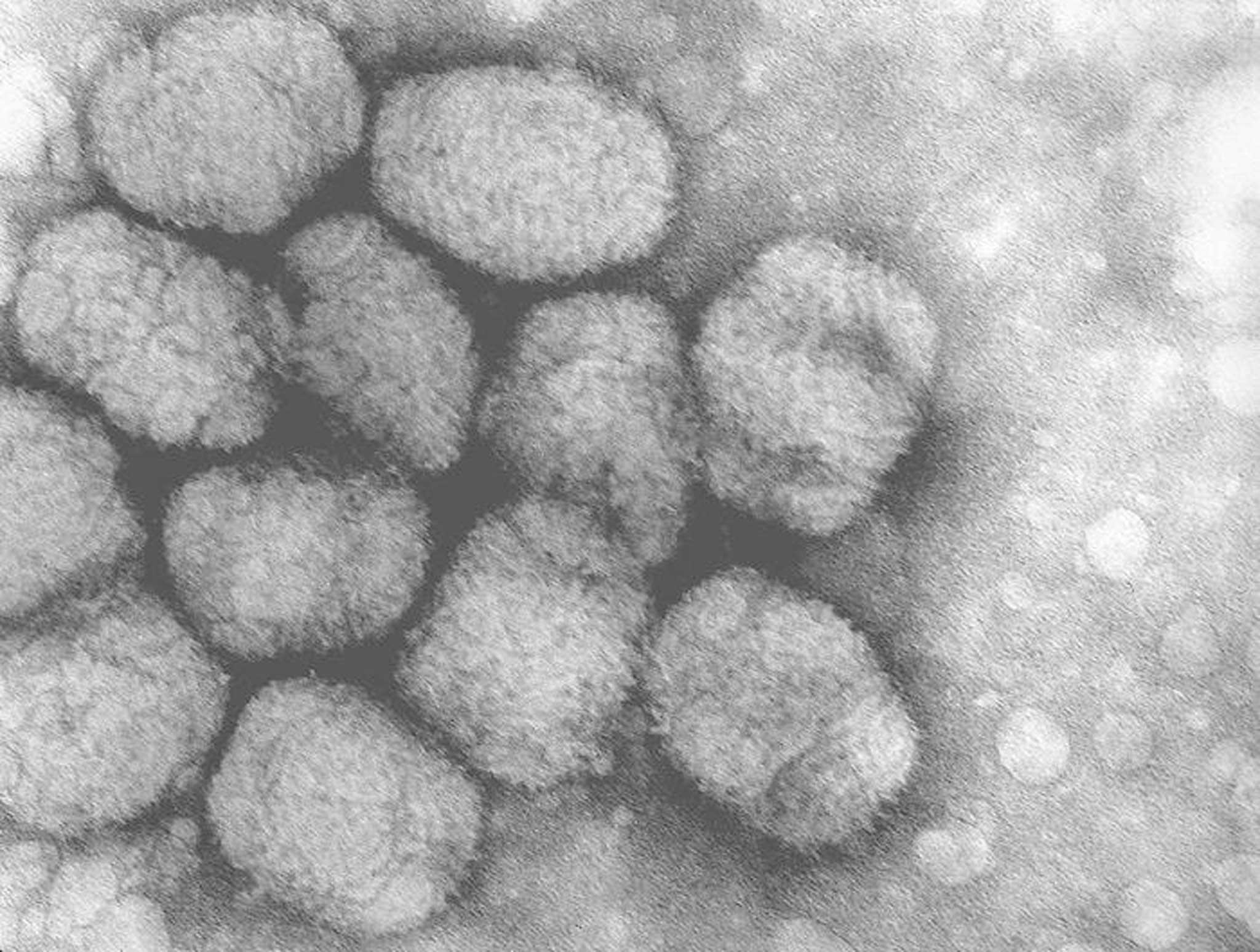

Smallpox was a killer disease in the 18th century. Infected people would become covered in horrible skin sores and often die a painful death. Those who recovered were left with terrible scars or poc marks on their skin. We now understand that it is caused by a virus (the variola virus). It infects the internal organs, causes severe blistering of the skin and death due to blood poisoning or secondary infections.

Edward Jenner is credited with the development of vaccination but in fact it was first introduced into England by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in 1721. She tried a method that was used in Turkey where people deliberately infected themselves with a mild form of smallpox. This was the first form of inoculation. Sadly, many people died from the smallpox they were using to protect themselves. Clearly something different needed to be done.

Jenner was a doctor who worked in Gloucestershire and the great advance he made was to notice that individuals who had contracted cowpox (the cow's equivalent of smallpox) rarely caught the deadly human version. In 1796 he deliberately infected an eight year old boy called James Phipps with the pus from a cowpox sore. The boy became ill with cowpox but recovered. He then infected him with the normally deadly smallpox. As Jenner had predicted the earlier infection with the cowpox actually protected the boy who never caught smallpox. The practice of modern vaccination was born and remains vitally important today, as was seen in recent years when responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lancets (knives) used by Jenner for vaccinations

After many more successful vaccinations, Jenner published his results in 1798. However, they were met with scepticism and many doctors still carried out the more dangerous practice of inoculation with live smallpox pus. It was not until 1840 that this dangerous practice was banned and in 1853 vaccination by Jenner's method was made compulsory. Protestors argued against compulsory vaccination, saying that it limited their personal choice; a similar debate to the one that raged around 2000 over the MMR vaccine.

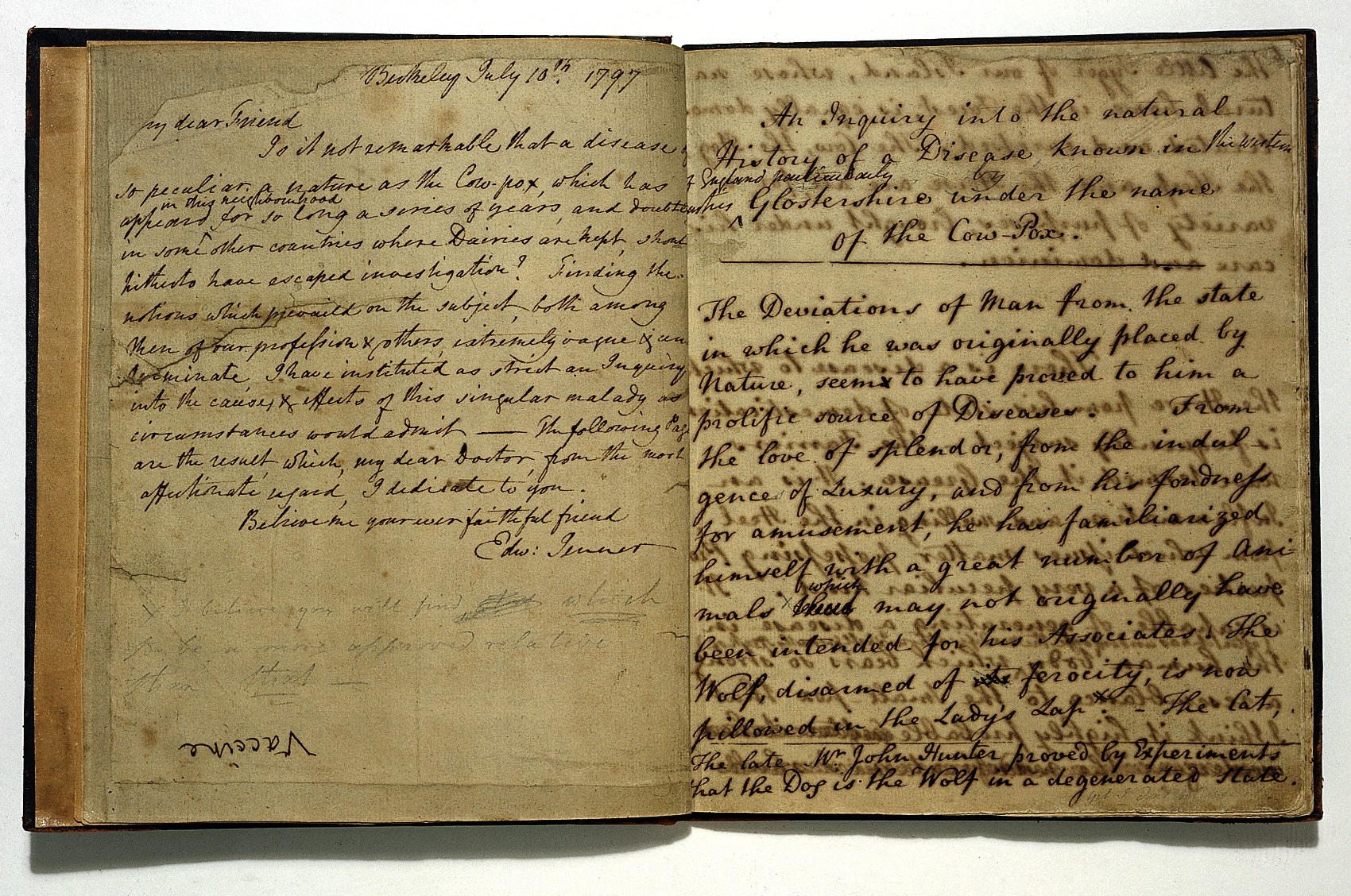

Jenner’s original paper ‘An inquiry into the natural history of a disease known in Glostershire under the name of Cow-Pox’

When Jenner tried his first vaccinations, the way microbes cause infectious diseases was not understood and he did not know about the immune system. We now understand how vaccination works.

Pathogens are microbes that cause disease. These can be viruses, like smallpox, or bacteria. If a small amount of the weakened, or inactive microbe is introduced into the body it stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies to fight off the disease. The immune system remembers the microbe and can defend the body against any live form of the microbe that it may encounter in the future. The person is said to be immune to the disease.

Find out more about vaccination and immune memory.

Nearly 300 years after Jenner's discovery, a programme of vaccination by the World Health Organisation (WHO) was started with the aim to completely eradicate the smallpox virus. It is estimated that smallpox killed 500 million people worldwide during the last century. The last case of naturally-transmitted smallpox was reported in Africa, in 1977. In 1980, the WHO officially announced the end of smallpox. There remain two highly-guarded stocks of the virus which are preserved for research purposes.

Smallpox pustules on a person’s leg

A clump of smallpox viruses viewed using an electron microscope. Over 13 million of these viruses would fit onto a full stop on this page.

Jenner's discovery has led to a greater understanding of the human immune system and vaccination programmes against diseases such as measles, mumps, polio and tuberculosis have improved the health of millions who need not fear these killer diseases.